(Editor’s Note: In light of continued free passes handed out to white police officers killing young black men across the country, it is appropriate to remember the infamous triple murder of civil rights workers in 1964. Most Americans have a whitewashed memory of that obscenity and the active role law enforcement played in both the crime and cover-up from the movie Mississippi Burning. To understand the current grief and anger of our black neighbors over the never ending murders of young blacks by law enforcement in this country, take a few minutes to read these two great articles. They are both examples of history we are not supposed to know – or at the very least, forget. – Mark L. Taylor)

By David Dennis Jr.

StillCrew (8/30/17)

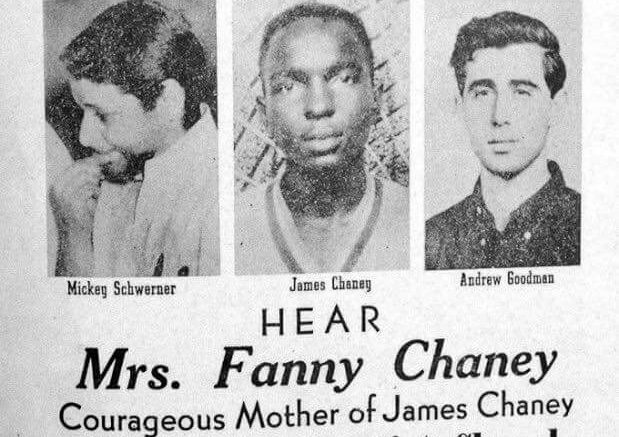

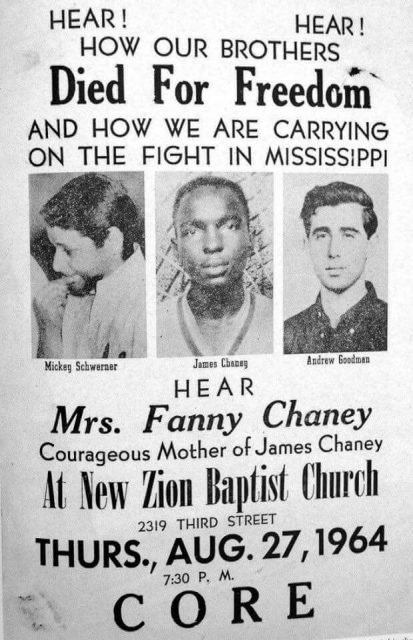

My father knew James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Mickey Schwerner were dead as soon as he got the call that they were missing. Their bodies weren’t found until 44 days later.

What happened between that phone call and the discovery of their bodies is a story that’s been bastardized by Hollywood, overlooked by those intent on ignoring America’s painful history and mired in misinformation. But anyone involved in the 1964 Freedom Summer in Mississippi knows one undeniable truth: Dick Gregory’s heroic battle with the FBI is the reason those bodies were found.

As Mississippi director for the Congress of Racial Equality, my dad, David Dennis, Sr., sent Goodman, Chaney and Schwerner to Longdale, MS to investigate a bombing at the Mount Zion church. What my father didn’t know at the time, but is sure of to this day, is that the KKK perpetrated the bombing to lure the three workers out and kill them. The Klan also prioritized Mickey Schwerner as a target. The young, fiery organizer was a dynamo at rallying black people to register to vote. Schwerner offended the Klan most of all because he was white. A traitor. And he was Jewish.

This is what terrorism looks like

Goodman, Chaney and Schwerner never made it back home after going to investigate the bombing. They never stood a chance . Reports since have indicated the three were arrested for speeding and placed in Neshoba County Jail until 10 pm. The three men were then followed from the jail by a group of Klansmen, including Deputy Sheriff Cecil Ray Price.

Anyone in Mississippi, my father included, believe the FBI always knew where the bodies were and only revealed where the bodies were after finding out Gregory also had that information.

The three activists were taken out of that station wagon and shot. Evidence indicates Andrew Goodman was buried alive next to the bodies of Chaney and Schwerner, in pre-prepared graves. There are also variations of the story that indicate that Schwerner and Goodman were shot once in the heart and died immediately and that James Chaney was tortured before being killed. The murders were a culmination of a thoroughly planned conspiracy that started with the burning down of Mt. Zion. A plan that went from the sheriff all the way down to local high school kids. This is what terrorism looks like. This is what war looks like.

My father planned to be with the three men when they took the trip to investigate the church bombing. He was supposed to be riding with them when they were murdered. However, his bronchitis got in the way and the three men convinced him to just go home and take care of it. So he reluctantly drove to Shreveport, LA to be with his mother and recover. That was the last time he saw them. My father awaited phone calls about the workers’ whereabouts as standard procedure any time he dispatched someone for an assignment. As soon as he learned the men hadn’t checked in, he knew they were dead. Everyone did. White and black.

However, the lynch mob that murdered the men hid the bodies under a dam built on the property of one of the Klansmen, turning the crime into a missing persons story. And since two of the missing men were white, it became national news.

For 44 days.

For 44 whole days, a country speculated on the whereabouts of the three slain workers. What haunts my father as much as anything else that happened with the three workers is the fact that during the search, more bodies turned up. Slain black men, lynched by the Klan. Local Klan members and even J. Edgar Hoover, who in May stated that “outsiders” coming to Mississippi for Freedom Summer would not be protected by the FBI, fanned the flames of conspiracy, insinuating the three men were Communists who were either killed by their own or fled to Cuba. It seemed likely that the bodies would never be found. If not for Dick Gregory.

‘They were afraid of something’

Dick Gregory was on a tour for “Ban the Bomb” disarmament efforts traveling through Europe and Asia, and was in Moscow when he heard the news that Goodman, Chaney and Schwerner were missing. He canceled the rest of his trip and was in Jackson, MS the same night. Once there, he immediately met with James Farmer, the head of CORE. Gregory, Farmer and a caravan of 16 cars headed to Philadelphia to try to find the men. Gregory, like everyone else, knew those men were dead.

“They knew without a shadow of a doubt that they had been killed,” Gregory said in a 1964 interview with Mississippi Eyewitness. Gregory’s caravan was stopped before being able to conduct a full search, but he was granted an audience with Sheriff Rainey. That’s what tipped Gregory off about the missing men.

“I thought it was kind of strange that they would even see us,” he continued to tell Mississippi Eyewitness. “Because no Mississippi law enforcement agency — no law enforcement agency in the world — would see anyone not connected with the case when they are in the middle of an investigation. So the fact that they would see us meant that they were afraid of something.”

Gregory noticed a nervousness in the meeting with the Neshoba County Sheriff Lawrence Rainey, who was a top conspirator to the murders …

*****

Ramparts Magazine: The Classic 1964 ‘Mississippi Eyewitness’ Report On The Murder Of Three Civil Rights Workers

(Editor’s Note: The article and link below takes you to every article from the 1964 special edition of Ramparts Magazine on the killing of the three civil rights workers in Mississippi. Each article is a powerful glimpse into the terrorist state of segregated Mississippi. Given the rise of the American Nazi movement and white supremacy it is important to know this firsthand – unvarnished – history. – Mark L. Taylor)

By Louis E. Lomax

Rampart Magazine (1964)

A DEATHLY DARK fell over the audience in Western College’s Peabody Hall. The young students gathered together looked at the two Negro men on the podium, men who welcomed them to the Mississippi Summer Project and then went on to promise them that they might get killed. But Robert Moses, a serious, intent master’s degree man from Harvard, and James Foreman, a college dropout who has given his all for the civil rights movement, were speaking from the depths of personal experience. And as the students talked and questioned on the rolling green Oxford, Ohio campus, Foreman and Moses never let them forget for one moment that death is always a possibility for those who venture into Mississippi as civil rights missionaries.

“Don’t expect them to be concerned with your constitutional rights,” Moses said. “Everything they (the white power structure) do in Mississippi is unconstitutional.”

“Don’t expect indoor plumbing,” James Foreman added, “get ready to do your business in outhouses.”

The assemblage, mostly middle class white Protestants and Jews, roared with laughter.

“Don’t laugh,” Moses screamed. “This is for real — like for life and death.”

“This is not funny,” Foreman added, “I may be killed. You may be killed. If you recognize that you may be killed — the question of whether you will be put in jail will become very, very minute.”

Andrew Goodman’s lip went dry. There was no longer a sophisticated “it can’t happen to me” grin on his face. Like most of the other college students from across the land who had volunteered to go into Mississippi, Goodman had been motivated by a combination of conviction and adventure. Now veterans of the struggle were making it plain that Mississippi was no playground for a Jewish liberal from New York who wanted to create a better world. Then R. Jess Brown, a graying and aging Negro lawyer from Jackson, Mississippi, walked to the podium to add fuel to the volunteer’s mounting fear.

“I am one of the three Mississippi lawyers — all of us Negroes –” Brown said, “who will even accept a case in behalf of a civil rights worker. Now get this in your heads and remember what I am going to say. They — the white folk, the police, the county sheriff, the state police — they are all waiting for you. They are looking for you. They are ready; they are armed. They know some of your names and your descriptions even now, even before you get to Mississippi. They know you are coming and they are ready. All I can do is give you some pointers on how to stay alive.”

“If you are riding, down the highway, say on Highway 80 near Bolton, Mississippi, and the police stop you, and arrest you, don’t get out and argue with the cops and say ‘I know my rights.’ You may invite that club on your bead. There ain’t no point in standing there trying to teach them some Constitutional Law at twelve o’clock at night. Go to jail and wait for your lawyer.”

THE MEETING ADJOURNED. A few of the volunteers gathered around Foreman, Moses and Attorney Brown to ask specific questions. The civil rights zealots got nothing in private that they had not been told in public: If you are going into Mississippi you must first raise — on your own — five hundred dollars bail money, list your next of kin, and then sit for a photograph with your identification number laced across your chest. These are the basic identifications the civil rights movement needs if a worker was arrested or killed.

The police did take notice of the station wagon and they knew that two of the three occupants were Michael Schwerner and James Chaney. The police, in unmarked cars, followed closely. Switching to the “Citizens Short Wave Band” that is used to keep the Ku Klux Klan and the White Citizens’ Council informed as to the movements of civil rights workers, the police broadcast the alarm. “They are headed north along 19. That nigger, Chaney, is driving. Over and out.”

“But if you are arrested and they start beating you,” Robert Moses added, “try and protect as much of your genital organs as possible.” Moses knew what be was talking about. He had been arrested scores of times; he had been beaten and each time his white tormentors aimed their booted feet at the genitals.

“Now,” James Foreman asked, “do you still want to go?”

The silence shouted “Yes”. But behind the silent “amen” there were all the gnawing doubts and apprehensions that plague any man, or woman, who knowingly marches into the jaws of danger.

“All I can offer is an intellectual justification for going into Mississippi,” one Harvard student said.

“I only want to do what I think is right to help others,” a Columbia University student added.

But it was Glenn Edwards, a twenty-one year old law student from the University of Chicago, who articulated what most of those involved really felt.

“I’m scared,” Edwards said, “a lot more scared than I was when I got here at Oxford for training. I am not afraid about a bomb going off in the house down there (in Mississippi) at night. But you can think about being kicked and kicked and kicked again. I know that I might be disfigured.”

Then, as the private give and take continued, the civil rights volunteers raised questions that gave the Mississippi veterans fits.

“Some of us have talked about interracial dating, once we get to Mississippi,” one girl told Robert Moses. “Is there any specific pattern you would have us follow?”

Moses eased by the question by saying there was simply nowhere in Mississippi for an interracial couple to go. John M. Pratt, a lawyer for the National Council of Churches, one of the sponsors of the project, bluntly warned the volunteers that Mississippi was waiting for just such a thing as interracial dating.

“Mississippi is looking for morals charges,” Pratt warned. “What might seem a perfectly innocent thing up North might seem a lewd and obscene act in Mississippi. I mean just putting your arm around someone’s shoulder in a friendly manner.”

But it was a tall, jet black veteran of the Mississippi struggle who rose and put the matter in precise perspective:

“Let’s get to the point,” he said (and his name must be withheld because he is one of the vital cogs in the Mississippi freedom movement). “This mixed couple stuff just doesn’t go in Mississippi. In two or three months you kids will be going, back home. I must live in Mississippi. You will be safe and sound, I’ve got to live there. Let’s register people to vote NOW; as for interracial necking, that will come later . . . if indeed it comes at all.”

Those who knew him say that Andrew Goodman was among the students who gathered for the private interviews. There is no record that he asked any questions or made any comments. Some of the volunteers were frightened by what they heard and they turned back, went home or took jobs as counsellors in safe summer camps in the non-south. Andrew Goodman was not among those who turned back.

A FEW DAYS LATER the civil rights volunteers, Goodman among them, left Oxford, Ohio, for specific assignments in Mississippi. …