By Danny Sjursen

TomDispach (10/12/17)

“This… thing, [the War on Drugs] this ain’t police work… I mean, you call something a war and pretty soon everybody gonna be running around acting like warriors… running around on a damn crusade, storming corners, slapping on cuffs, racking up body counts… pretty soon, damn near everybody on every corner is your f**king enemy. And soon the neighborhood that you’re supposed to be policing, that’s just occupied territory.” — Major “Bunny” Colvin, season three of HBO’s The Wire

I can remember both so well.

2006: my first raid in South Baghdad. 2014: watching on YouTube as a New York police officer asphyxiated — murdered — Eric Garner for allegedly selling loose cigarettes on a Staten Island street corner not five miles from my old apartment. Both events shocked the conscience.

It was 11 years ago next month: my first patrol of the war and we were still learning the ropes from the army unit we were replacing. Unit swaps are tricky, dangerous times. In Army lexicon, they’re known as “right-seat-left-seat rides.” Picture a car. When you’re learning to drive, you first sit in the passenger seat and observe. Only then do you occupy the driver’s seat. That was Iraq, as units like ours rotated in and out via an annual revolving door of sorts. Officers from incoming units like mine were forced to learn the terrain, identify the key powerbrokers in our assigned area, and sort out the most effective tactics in the two weeks before the experienced officers departed. It was a stressful time.

Those transition weeks consisted of daily patrols led by the officers of the departing unit. My first foray off the FOB (forward operating base) was a night patrol. The platoon I’d tagged along with was going to the house of a suspected Shiite militia leader. (Back then, we were fighting both Shiite rebels of the Mahdi Army and Sunni insurgents.) We drove to the outskirts of Baghdad, surrounded a farmhouse, and knocked on the door. An old woman let us in and a few soldiers quickly fanned out to search every room. Only women — presumably the suspect’s mother and sisters — were home. Through a translator, my counterpart, the other lieutenant, loudly asked the old woman where her son was hiding. Where could we find him? Had he visited the house recently? Predictably, she claimed to be clueless. After the soldiers vigorously searched (“tossed”) a few rooms and found nothing out of the norm, we prepared to leave. At that point, the lieutenant warned the woman that we’d be back — just as had happened several times before — until she turned in her own son.

For nearly five decades, Americans have been mesmerized by the government’s declarations of “war” on crime, drugs, and — more recently — terror. In the name of these perpetual struggles, apathetic citizens have acquiesced in countless assaults on their liberties.

I returned to the FOB with an uneasy feeling. I couldn’t understand what it was that we had just accomplished. How did hassling these women, storming into their home after dark and making threats, contribute to defeating the Mahdi Army or earning the loyalty and trust of Iraqi civilians? I was, of course, brand new to the war, but the incident felt totally counterproductive. Let’s assume the woman’s son was Mahdi Army to the core. So what? Without long-term surveillance or reliable intelligence placing him at the house, entering the premises that way and making threats could only solidify whatever aversion the family already had to the U.S. Army. And what if we had gotten it wrong? What if he was innocent and we’d potentially just helped create a whole new family of insurgents?

Though it wasn’t a thought that crossed my mind for years, those women must have felt like many African-American families living under persistent police pressure in parts of New York, Baltimore, Chicago, or elsewhere in this country. Perhaps that sounds outlandish to more affluent whites, but it’s clear enough that some impoverished communities of color in this country do indeed see the police as their enemy. For most military officers, it was similarly unthinkable that many embattled Iraqis could see all American military personnel in a negative light. But from that first raid on, I knew one thing for sure: we were going to have to adjust our perceptions — and fast. Not, of course, that we did.

Years passed. I came home, stayed in the Army, had a kid, divorced, moved a few more times, remarried, had more kids — my Giants even won two Super Bowls. Suddenly everyone had an iPhone, was on Facebook, or tweeting, or texting rather than calling. Somehow in those blurred years, Iraq-style police brutality and violence — especially against poor blacks — gradually became front-page news. One case, one shaky YouTube video followed another: Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Tamir Rice, Philando Castile, and Freddie Gray, just to start a long list. So many of the clips reminded me of enemy propaganda videos from Baghdad or helmet-cam shots recorded by our troopers in combat, except that they came from New York, or Chicago, or San Francisco.

Brutal Connections

As in Baghdad, so in Baltimore. It’s connected, you see. Scholars, pundits, politicians, most of us in fact like our worlds to remain discretely and comfortably separated. That’s why so few articles, reports, or op-ed columns even think to link police violence at home to our imperial pursuits abroad or the militarization of the policing of urban America to our wars across the Greater Middle East and Africa. I mean, how many profiles of the Black Lives Matter movement even mention America’s 16-year war on terror across huge swaths of the planet? Conversely, can you remember a foreign policy piece that cited Ferguson? I doubt it.

Nonetheless, take a moment to consider the ways in which counterinsurgency abroad and urban policing at home might, in these years, have come to resemble each other and might actually be connected phenomena …

(Major Danny Sjursen, a TomDispatch regular, is a U.S. Army strategist and former history instructor at West Point. He served tours with reconnaissance units in Iraq and Afghanistan. He has written a memoir and critical analysis of the Iraq War, Ghost Riders of Baghdad: Soldiers, Civilians, and the Myth of the Surge. Note: The views expressed in this article are those of the author, expressed in an unofficial capacity, and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.)

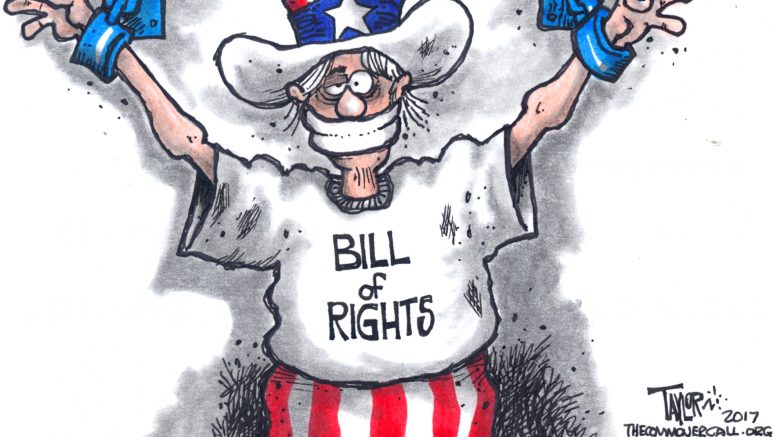

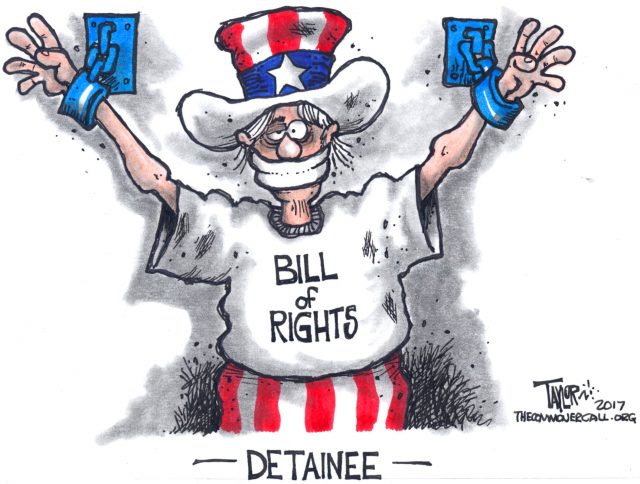

(Commoner Call cartoon by Mark L. Taylor, 2017. Open source and free to use with link to www.thecommonercall.org )

*****

Here’s Why The Bill Of Rights Is Essential For The Freedom Of Every Citizen Of The United States

The Bill of Rights Institute

The first 10 amendments to the Constitution make up the Bill of Rights. Written by James Madison in response to calls from several states for greater constitutional protection for individual liberties, the Bill of Rights lists specific prohibitions on governmental power. The Virginia Declaration of Rights, written by George Mason, strongly influenced Madison.

One of the many points of contention between Federalists and Anti-Federalists was the Constitution’s lack of a bill of rights that would place specific limits on government power. Federalists argued that the Constitution did not need a bill of rights, because the people and the states kept any powers not given to the federal government. Anti-Federalists held that a bill of rights was necessary to safeguard individual liberty. …