“I would rather a thousand times be a free soul in jail than to be a sycophant and coward in the streets.”

By Marlene Martin

SocialistWorker.org (6/15/18)

One hundred years ago [1918], Eugene V. Debs spoke out against the First World War in a speech in Canton, Ohio — and was given a 10-year prison sentence for it. recounts one of the most famous moments in the history of socialism in the U.S.

THE FIRST thing Eugene V. Debs did when he walked to the stage in Canton, Ohio, on the afternoon of June 16, 1918, was to gesture toward the courthouse building where he had just been visiting fellow socialists imprisoned for speaking out against the war.

“I have just returned from a visit over yonder where three of our most loyal comrades are paying the penalty for their devotion to the cause of the working class,” he told the crowd of 1,200 who had come to hear the best-known leader of the Socialist Party and its presidential candidate four times before.

To shouts and cheers, Debs said: “I am proud of them; they are there for us, and we are here for them. Their lips, though temporarily mute, are more eloquent than ever before, and their voice, though silent, is heard around the world.”

Those words were prophetic about Debs himself. He was arrested and prosecuted for making that speech in Canton on charges of sedition under the Espionage Act. Found guilty, he was sentenced to 10 years in a federal prison.

But Debs, like his comrades in Canton, was “heard around the world” and for generations to come, despite the government’s temporary success in silencing him. One hundred years later, his Canton antiwar speech is a powerful and inspiring statement of the socialist principles of internationalism and opposition to imperialist war.

*****

WORRIED THAT sentiment against the First World War would grow, Congress looked for a way to enforce support for it. So a year before Debs’ speech, it passed the Espionage Act, which made it a criminal offense to publicly oppose the war (by the way, this law is still on the books).

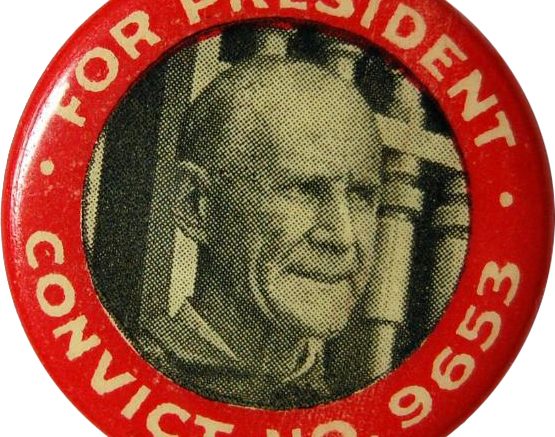

Eugene V. Debs gives his antiwar speech that sent him to prison in Canton, Ohio, June 15, 1918.

Within two weeks of the speech, Debs — who was already known to the Democratic Wilson administration as “a traitor to his country” — was indicted and charged with sedition.

By the time Debs spoke in Canton, many socialists comrades had already been arrested and jailed. He told the crowd that he had to be careful with what he said because there were “certain limitations placed upon the right of free speech.”

Still, he said, “I may not be able to say all I think; but I am not going to say anything that I do not think. I would rather a thousand times be a free soul in jail than to be a sycophant and coward in the streets.”

Debs was the most popular socialist of his time. He was beloved for his ability to put into words the cause of the working-class movement and the vision of socialism, with so much passion and animation.

In a speech he once gave to a majority Polish-speaking audience, Debs couldn’t understand why the audience was so responsive when they probably understood little of what he said. A Polish socialist explained simply: “Debs talks to us with his hands, out of his heart, and we all understood everything he said.”

James Cannon, who became a main leader of the socialist movement in the years that followed, heard Debs speak several times and described the effect he had on people, including himself:

“He was a man of many talents, but he played his greatest role as an agitator, stirring up the people and sowing the seed of socialism far and wide. He was made for that, and he gloried in it…to wake people up, to shake them loose from habits of conformity and resignation, to show them a new road.”

Debs had come to socialism via trade unionism. As the head of the American Railway Union, he became the leader of the 1894 strike against the Pullman Palace Car Company — a huge struggle just south of Chicago that pitted thousands of workers against a greedy and paternalistic employer.

The strike lost, and Debs was convicted and sent to jail for six months for defying an injunction against the union. Because he stood firmly with the workers and was willing to go to jail for it, Debs won great respect and admiration.

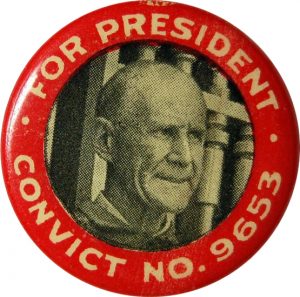

In his jail cell, Debs received and read books, pamphlets and letters sent to him from socialists everywhere. He read Capital and became a convinced Marxist. Following his release, he joined the socialist movement, running five times for president between 1900 and 1920. In 1920, while he was in jail for the speech in Canton, he won almost a million votes.

DEBS’ CANTON speech expressed the source of his unwavering devotion to the working class:

“I am suspicious of leaders, and especially of the intellectual variety. Give me the rank and file every day in the week.

“If you go to the city of Washington, and you examine the pages of the Congressional Directory, you will find that almost all of those corporation lawyers and cowardly politicians, members of Congress, and misrepresentatives of the masses — you will find that almost all of them claim, in glowing terms, that they have risen from the ranks to places of eminence and distinction.

“I am very glad I cannot make that claim for myself. I would be ashamed to admit that I had risen from the ranks. When I rise, it will be with the ranks, and not from the ranks.”

Those condemned to fight the wars

Debs also emphasized that it was these very ranks that were called upon to fight the wars, and not the “master class” that “always declared the wars,” but never had to fight them: “[T]he subject class has always fought the battles,” Debs said. “The master class has all to gain and nothing to lose, while the subject class has had nothing to gain and all to lose — especially their lives.”

This statement of socialism’s principled opposition to imperialist war came as the majority of the socialist movement had collapsed into support for their own governments in the First World War. In Europe, revolutionaries such as the Bolsheviks in Russia were a small minority in opposing the war when it began in 1914.

Because of the U.S.’s late entry into the war, the Socialist Party didn’t face the same challenges, but by the time of Debs’ speech, many prominent socialists had left the party over this question. …