By Matt Taibbi

Rolling Stone (5/1/18)

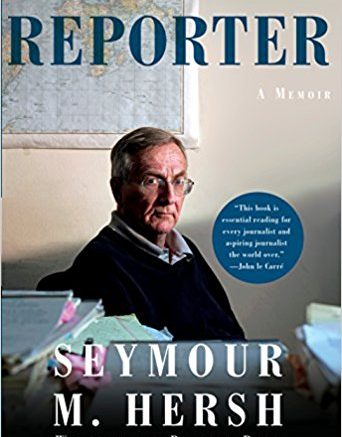

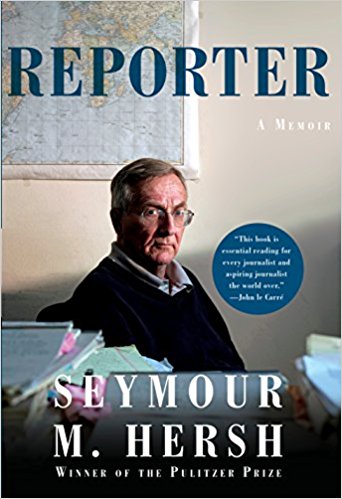

Late in his new memoir, Reporter, muckraking legend Seymour Hersh recounts an episode from a story he wrote for the New Yorker in 1999, about the Israeli spy Jonathan Pollard.

Bill Clinton was believed to be preparing a pardon for Pollard. This infuriated the rank and file of the intelligence community, who now wanted the press to know just what Pollard had stolen and why letting him free would be, in their eyes, an outrage.

“Soon after I began asking questions,” Hersh writes, “I was invited by a senior intelligence official to come have a chat at CIA headquarters. I had done interviews there before, but always at my insistence.”

He went to the CIA meeting. There, officials dumped a treasure trove of intelligence on his desk and explained that this material – much of which had to do with how we collected information about the Soviets – had been sold by Pollard to Israel.

“One of my quirks has been to keep track of the retirement of senior generals and admirals; those who did not get to the top invariably had a story to tell in explaining why.”

On its face, the story was sensational. But Hersh was uncomfortable. “I was very ambivalent about being in the unfamiliar position of carrying water for the American intelligence community,” he wrote. “I, who had worked so hard in my career to learn the secrets, had been handed the secrets.”

This offhand line explains a lot about what has made Hersh completely embody what it means to be a reporter. The great test is being able to get information powerful people don’t want you to have. A journalist who is handed something, even a very sensational something, should feel nervous, sick, ambivalent. Hersh never stopped feeling that way, remaining an iconoclast and a thorn in the side of officialdom to this day.

Hersh became famous in the late-’60s and early-’70s, at a time when the country was experiencing violent domestic upheaval and investigative reporters were for the first time celebrated like rock stars.

Hersh was best known back then for his reporting on American atrocities in Vietnam, in particular the massacre of hundreds of unarmed Vietnamese in the village of My Lai. The story did a great deal to puncture the myth of American beneficence in Southeast Asia.

A significant theme of Hersh’s work is that Americans are human beings, not immune from the horrific temptations of power that throughout history have afflicted and shamed those who have dominion over others. …

*****

Seymour Hersh’s New Memoir Is A Fascinating, Flabbergasting Masterpiece

By Jon Schwarz

the Intercept (6/2/18)

AT THE BEGINNING of Seymour Hersh’s new memoir, “Reporter,” he tells a story from his first job in journalism, at the City News Bureau of Chicago.

City News stationed a reporter at Chicago’s police headquarters 24 hours a day to cover whatever incidents were radioed in. Hersh, then in his early 20s, was responsible for the late shift. One night, he writes, this happened:

“Two cops called in to report that a robbery suspect had been shot trying to avoid arrest. The cops who had done the shooting were driving in to make a report. … I raced down to the basement parking lot in the hope of getting some firsthand quotes before calling in the story. The driver – white, beefy, and very Irish, like far too many Chicago cops then – obviously did not see me as he parked the car. As he climbed out, a fellow cop, who clearly had heard the same radio report I had, shouted something like, “So the guy tried to run on you?” The driver said, “Naw, I told the nigger to beat it and then I plugged him.””

What happened then? Did Hersh, who would go on to uncover the My Lai massacre in Vietnam and become one of the greatest investigative journalists in U.S. history, sprint to his publication and demand that it run this explosive scoop?

There’s a tale about Lyndon B. Johnson on page 201 that everyone deserves to encounter without spoilers. Even Donald Trump has never expressed his contempt for the media with such, let’s say, vivacity. Journalists will come away from it extremely grateful that all Trump does is tweet.

No. Hersh spoke to his editor, who told him to do nothing, since it would be his word against the police. He didn’t try to interview the responsible cop or his partner, or dig much further. Instead, he gave up on it and soon headed off to do his required service in the Army, “full of despair at my weakness and the weakness of a profession that dealt so easily with compromise and self-censorship.”

If Hersh were a superhero, this would be his origin story. Two hundred and seventy-four pages after the Chicago anecdote, he describes his coverage of a massive slaughter of Iraqi troops and civilians by the U.S. in 1991 after a ceasefire had ended the Persian Gulf War. America’s indifference to this massacre was, Hersh writes, “a reminder of the Vietnam War’s MGR, for Mere Gook Rule: If it’s a murdered or raped gook, there is no crime.” It was also, he adds, a reminder of something else: “I had learned a domestic version of that rule decades earlier” in Chicago. …

Semyour Hersh’s “Reporter” demonstrates that Hersh has derived three simple lessons:

-

The powerful prey mercilessly upon the powerless, up to and including mass murder.

-

The powerful lie constantly about their predations.

-

The natural instinct of the media is to let the powerful get away with it.