By Tom Crofton

The Commoner Call (5/8/17)

The first thing that comes to mind when thinking about unions is wages. The non-union, merit-based system says that each deserves wages based on some type of objective metric. This system requires confidentiality (you do not want employees comparing their individual deals) and rewards those who find ways to play the system, though not necessarily fairly. A major flaw in this system is that most jobs do not have a clear metric for comparison. Teachers for example have been singled out for some type of merit pay. How do you rate the work of an art teacher, or a gym teacher, much less a math teacher with students of varying abilities or disabilities?

A cornerstone of union organizing is the benchmark rate, where we all start on an even playing field kept in place through our solidarity with each other, and a contract that legally binds our employer to meet his side of the bargain. In construction, corresponding work rules prevent individuals from bringing their own expensive equipment to a job to gain an advantage over others in the eyes of the employer. The Company provides the working conditions and meets minimal standards for health and safety. Attempts to erode these standards have existed with the rise of “independent contractors” and “associates”.

Some non-union firms such as WalMart have encouraged their employees to stay a while after they punch-out, to help tidy up the store and re-hang clothing on the racks. The unspoken implication is that the “associates” who comply have a better chance of not being laid off when that time comes. Less-than-employee-status workers are used to undercut the benchmark of the industry, and are often illegal, and usually violate IRS protections. The benchmark helps all workers. Even those running just beneath it are benefiting from its existence: they would make much less in a race to the bottom without it.

The struggle to bring sustainability and sanity to our world, country, and state can start here in rural WI. We can develop a new economy that does not require the exploitation of the planet and its less-well-off people. We require the solidarity of collective bargaining and we need to extend that solidarity to the rest of the working world.

The New Deal officially supported the idea of unions. The build-up to WWII brought so much activity that unions were considered an effective way to control a growing, skilled, labor force. As wages grew and demand for war materials increased, employers realized that buying benefits in bulk was cheaper than paying cash directly to the employees. While we hear many complaints about the employer-based health insurance system in this country, the business community developed it to save money and attract workers.

Wages are the largest piece of most compensation packages that also include the value of healthcare, pension, training, vacation, sick days, and union fees. “Cash on the check” is the phrase most heard during negotiations for new contracts. There is a wide range of wage rates and compensation packages in America that stems from the fractured history of union development and the varied regional, historical effectiveness of union organizing.

The early efforts of unionization in this country had their roots in the craft guilds of Europe, where journeymen taught apprentices who often were required to do scutt work for years to keep them from competing with their skilled trainers. A young carpenter/cabinet maker in Norway (my grandfather) was only allowed to build caskets so his work would be buried and would not compete with his master’s work.

Class consciousness, American materialism, and the need for many to feel “above” someone else have prevented industry-wide organizing along the lines of the Industrial Workers of the World (The Wobblies). The IWW concept was to build one big union for all and to take control of production. Since the workers know how to run the equipment, they can cut out the inefficiencies and waste of management and use their production to build a classless society, with plenty for all. This effort was derailed through violence by the private armies of the capitalists and the public ones of bought-off politicians. The result was a fragmented, more easily controllable labor system.

Friction in labor

The construction trades, for example have at least 18 separate unions with different compensation packages, pension, and health plans. Large industries such as steel making were torn apart by the inflexibility of the many unions to adapt to new technology and the rise of non-union plants in low-wage “right-to-work” states and developing countries. Many craft unions fight among themselves, stealing work that had traditionally been in the “jurisdiction” of another trade. The American Federation of Labor (AFL) was organized to coordinate (but not merge) the separate crafts but left the lowest level workers unorganized. Efforts to raise the wages and working conditions of the lowest level industrial workers (lumpenproletariate in Marxist Terms) spawned the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). Both of these organizations fought the companies for their members but never attempted to organize to move the economic system past capitalism, towards “worker control of production”. They instead wanted a permanent role parallel to the employers. Their merger solidified that role and the work of the Wobblies to build a better, fairer system “within the shell of the old” faded, as material wealth helped “raise all boats”, and American Exceptionalism took hold.

Union workers from the 60’s until now have supported the post-WWII wars of the new American Empire and feel little solidarity with the workers of the countries we fight in. A great deal of this tragic consequence stems from the support of the AFL-CIO leadership for capitalism and its political hold over developing countries. The AFL was used by the CIA and big business to tamp down political dissent in South America in the 20th Century. An unholy alliance between the leadership of the Banana Republics, corporate interests, both political parties, and the American labor movement remains to this day. Nationalism trumping worker solidarity is nothing new.

Europe in the early 1900’s was rife with socialist revolutionary movements that transcended national borders. The assassination of the Archduke of Austria kicked off a series of treaties among corrupt, failing monarchies that were able to raise their nationalistic rhetoric to a fever pitch, tricking working people who had everything else in common, to drop their solidarity and pick up weapons to kill each other by the millions. We now do this with drones from the other side of the globe so we, the American workers, don’t have to get up close and personal with it.

The struggle to bring sustainability and sanity to our world, country, and state can start here in rural WI. We can develop a new economy that does not require the exploitation of the planet and its less-well-off people. We require the solidarity of collective bargaining and we need to extend that solidarity to the rest of the working world. Living wages, where a person earns enough to support a family without additional help, health care for all, and retirement security are all reachable goals. The planet has plenty of resources if we learn to not be wasteful. Acting on these ideas locally and not allowing the old “divide and conquer” con game splitting public and private, blue and white collar, black and white, female and male to be effective are all personal choices, we can each make.

Voting with our wallets and purchasing union-made and fair-trade items are small but very necessary steps to take. Developing a working peoples’ political party is a tough one that may be required too.

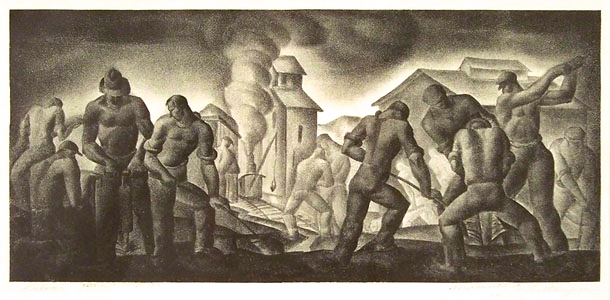

(Artwork from FDR Presidential Library and Museum.)