It’s a scene that feels ever more familiar these days — until the police actually do fire on the crowd. Panicked protesters flee, sobbing, bleeding, dying.

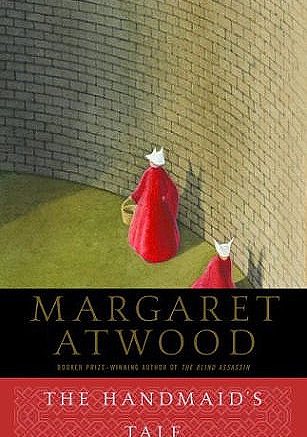

The scene is from Hulu’s original series “The Handmaid’s Tale,” an adaptation of Margaret Atwood’s best-selling 1985 novel of the same name, and though the material is more than 30 years old, the series feels almost like a tornado warning when a mile-wide twister is roaring down the drive.

For those who have marched, more recently or in decades past, this episode, in particular, is a reminder of what waits on the other side of complacency.

Atwood’s book, which once again became a best-seller after the election, tells the story of Offred (Elisabeth Moss in the series), a so-called handmaiden in the Republic of Gilead. Gilead is what the United States has become after an attack that killed Congress and the president; though blamed on Islamic terrorists, the attack was actually the work of the Jacobites, Christian fundamentalists who suspend the Constitution and establish a theocracy based on the subjugation of women and warped interpretations of the Old Testament.

Fertile women, who are in short supply due to the effects of pollution, are treated as nothing more than ambulatory wombs. Members of religious sects other than the Jacobites are subject to death. LGBTQ people are labeled gender traitors and also subject to death. Abortion providers: death.

There was a time in American history when this world didn’t seem so foreign, before Roe v. Wade, before Title IX. But for the last 20 years or so, large swaths of the U.S. population felt as though we were headed further and further away from such a path.

No longer. …

*****

Margaret Atwood on What ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’ Means In The Age Of Trump

By Margaret Atwood

The New York Times (4/10/17)

In the spring of 1984 I began to write a novel that was not initially called “The Handmaid’s Tale.” I wrote in longhand, mostly on yellow legal notepads, then transcribed my almost illegible scrawlings using a huge German-keyboard manual typewriter I’d rented.

The keyboard was German because I was living in West Berlin, which was still encircled by the Berlin Wall: The Soviet empire was still strongly in place, and was not to crumble for another five years. Every Sunday the East German Air Force made sonic booms to remind us of how close they were. During my visits to several countries behind the Iron Curtain — Czechoslovakia, East Germany — I experienced the wariness, the feeling of being spied on, the silences, the changes of subject, the oblique ways in which people might convey information, and these had an influence on what I was writing. So did the repurposed buildings. “This used to belong to . . . but then they disappeared.” I heard such stories many times.

The control of women and babies has been a feature of every repressive regime on the planet.

Having been born in 1939 and come to consciousness during World War II, I knew that established orders could vanish overnight. Change could also be as fast as lightning. “It can’t happen here” could not be depended on: Anything could happen anywhere, given the circumstances.

By 1984, I’d been avoiding my novel for a year or two. It seemed to me a risky venture. I’d read extensively in science fiction, speculative fiction, utopias and dystopias ever since my high school years in the 1950s, but I’d never written such a book. Was I up to it? The form was strewn with pitfalls, among them a tendency to sermonize, a veering into allegory and a lack of plausibility. If I was to create an imaginary garden I wanted the toads in it to be real. One of my rules was that I would not put any events into the book that had not already happened in what James Joyce called the “nightmare” of history, nor any technology not already available. No imaginary gizmos, no imaginary laws, no imaginary atrocities. God is in the details, they say. So is the Devil.

Back in 1984, the main premise seemed — even to me — fairly outrageous. Would I be able to persuade readers that the United States had suffered a coup that had transformed an erstwhile liberal democracy into a literal-minded theocratic dictatorship? In the book, the Constitution and Congress are no longer: The Republic of Gilead is built on a foundation of the 17th-century Puritan roots that have always lain beneath the modern-day America we thought we knew. …

*****

Margaret Atwood Responds To Cast’s Claim That ‘Handmaid’s Tale’ Isn’t A Feminist Story

By Katherin Brooks

The Gaurdian (4/22/17)

It’s difficult to talk about “The Handmaid’s Tale,” Hulu’s adaptation of Margaret Atwood’s famous dystopia, without bringing up the story’s eerie relevance to contemporary politics. It is, after all, centered on a dictatorial regime hellbent on policing women’s bodies.

This was certainly the case during a panel discussion at Tribeca Film Festival on Friday night, during which many of the show’s cast and crew were asked how they felt about the political aspects of the series, set to premiere on April 26. When asked whether or not the story’s feminist themes in particular were part of the reason some of the actors were attracted to the project, the answers were somewhat surprising.

“Any story about a powerful woman owning herself in any way is automatically deemed feminist,” Madeline Brewer, who plays handmaid Janine, told audiences after a screening of the show’s first episode. “This is a story about a woman. I don’t think this is feminist propaganda. I think this is a story about women and about humans. The three people hanging on the wall were all men. This story affects all people.”

“I really echo what Maddie said before,” Elizabeth Moss, who plays Offred, said. “It’s not a feminist story, it’s a human story, because women’s rights are human rights. I never intended to play Peggy [from ‘Mad Men’] as a feminist and I never expected to play Offred as a feminist.”

A few members of the audience, including MTV culture writer Rachel Handler, took to Twitter to express their concern with Moss and Brewer’s claims. …

*****

Three Women From Three Generations Read & Reflect On Handmaid’s Tale