By Stephanie O’Neil

NPR 9111/18/18)

When Kathy Klute-Nelson heads out on a neighborhood walk, she often takes her two dogs — Kona, a boxer, and Max, a small white dog of questionable pedigree who barrels out the front door with barks of enthusiasm.

The 64-year-old resident of Costa Mesa, Calif., says she was never one to engage in regular exercise — especially after a long day of work. But about three years ago, her employer, the Auto Club of Southern California, made her and her colleagues an offer she couldn’t refuse: Wear a Fitbit, walk every day and get up to $300 off your yearly health insurance premiums.

“I thought, ‘Why don’t I try this?’ ” Klute-Nelson says. ” ‘Maybe it’ll motivate me.’ And it really did. You know, you get into little groups and you start walking around and come back and feel better.”

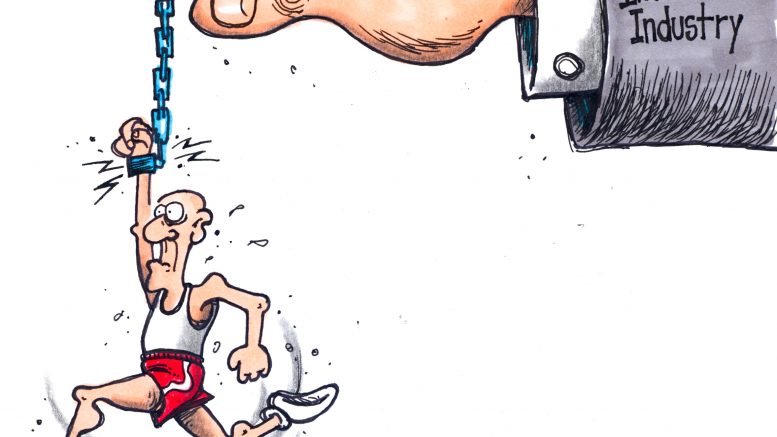

If Congress ever repeals the Affordable Care Act, insurers could use the fitness data they’re collecting today to deny you coverage based on a medical condition that your tracker detects.

Today she’s among the millions of Americans who use wearable fitness devices such as Fitbits that track an assortment of personal information — everything from movement and sleep patterns to blood pressure and heartbeats per minute.

This year, an estimated 6 million workers worldwide will receive wearable fitness trackers as part of workplace wellness programs. That’s up from about 2 million in 2016, according to ABI Research, a market research firm.

Many of these voluntary programs offer workers free or discounted wearable trackers and annual financial incentives that range from about $100 to more than $2,000, depending on the company.

For Klute-Nelson, the incentive money does the trick.

“It really encourages you to get up and move,” she says. “I mean, how many times do you get to the end of the day, you’re in the office and you think, ‘Gosh, I didn’t really get up from my desk at all today.’ ”

For companies, encouraging workers to get fit makes financial sense, says UnitedHealthcare spokesman Will Shanley. Healthy workers should cost the insurer less and can be more productive. The health insurance giant offers employer-sponsored plans that promote three walking goals with an easy-to-remember acronym.

“It’s called F.I.T.,” he says. “Frequency, intensity and tenacity.”

People who move frequently, walk with moderate intensity and log 10,000 steps each day can earn more than $1,000 a year toward health care spending. And, Shanley says, it’s not just the already fit who are signing up for the program.

“The participation rates for people with chronic conditions — diabetes in particular — is actually significantly higher than for people without those conditions,” he says.

But just how much fitness trackers contribute — if at all — to better health and lower health care spending isn’t yet known. …

Link to Story and 4-Minute Audio

(Commoner Call cartoon by Mark L. Taylor, 2018. Open source and free for non-derivative use with link toe www.thecommonercall.org )

*****

Insurance, Wearables And The Future Of Healthcare

By Enrique Dans

Forbes (9/21/18)

John Hancock, one of the largest and oldest insurers in the United States, owned since 2004 by Canada’s Manulife, has announced it will stop selling traditional life insurance and will only market interactive policies that record the exercise activities and data of health of its customers through wearables such as Fitbit or Apple Watch. The company will sell this type of policy through its subsidiary Vitality, finalizing in 2019 the conversion of its entire portfolio of policies to the new procedure.

These types of policies are becoming increasingly popular in markets such as South Africa, the United Kingdom and the United States, and are sold as an advantage both for users, who have an additional incentive to lead a healthier life, and for insurers, who get a portfolio of clients with healthier habits who tend to live longer and make fewer claims. Its detractors argue, however, that insurer may try to optimize their portfolios based on the data obtained, trying to offer less attractive conditions to those with variables indicating a higher risk.

As technology improves the ability of devices to record data related to exercise and health, more companies are seeing the opportunities this new approach may offer. …

*****

Health Insurers Vacuum Up Volumes Of Personal Information About You That Could Raise Your Rates

“We have a health privacy machine that’s in crisis.”

By Marshal Allen

ProPublica & NPR (7/17/18)

This story was co-published with NPR.

To an outsider, the fancy booths at last month’s health insurance industry gathering in San Diego aren’t very compelling. A handful of companies pitching “lifestyle” data and salespeople touting jargony phrases like “social determinants of health.”

But dig deeper and the implications of what they’re selling might give many patients pause: A future in which everything you do — the things you buy, the food you eat, the time you spend watching TV — may help determine how much you pay for health insurance.

With little public scrutiny, the health insurance industry has joined forces with data brokers to vacuum up personal details about hundreds of millions of Americans, including, odds are, many readers of this story. The companies are tracking your race, education level, TV habits, marital status, net worth. They’re collecting what you post on social media, whether you’re behind on your bills, what you order online. Then they feed this information into complicated computer algorithms that spit out predictions about how much your health care could cost them.

Are you a woman who recently changed your name? You could be newly married and have a pricey pregnancy pending. Or maybe you’re stressed and anxious from a recent divorce. That, too, the computer models predict, may run up your medical bills.

Are you a woman who’s purchased plus-size clothing? You’re considered at risk of depression. Mental health care can be expensive.

Low-income and a minority? That means, the data brokers say, you are more likely to live in a dilapidated and dangerous neighborhood, increasing your health risks.

Oceans of personal data

“We sit on oceans of data,” said Eric McCulley, director of strategic solutions for LexisNexis Risk Solutions, during a conversation at the data firm’s booth. And he isn’t apologetic about using it. “The fact is, our data is in the public domain,” he said. “We didn’t put it out there.”

Insurers contend they use the information to spot health issues in their clients — and flag them so they get services they need. And companies like LexisNexis say the data shouldn’t be used to set prices. But as a research scientist from one company told me: “I can’t say it hasn’t happened.”

At a time when every week brings a new privacy scandal and worries abound about the misuse of personal information, patient advocates and privacy scholars say the insurance industry’s data gathering runs counter to its touted, and federally required, allegiance to patients’ medical privacy. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, or HIPAA, only protects medical information.

“We have a health privacy machine that’s in crisis,” said Frank Pasquale, a professor at the University of Maryland Carey School of Law who specializes in issues related to machine learning and algorithms. “We have a law that only covers one source of health information. They are rapidly developing another source.”

Patient advocates warn that using unverified, error-prone “lifestyle” data to make medical assumptions could lead insurers to improperly price plans — for instance raising rates based on false information — or discriminate against anyone tagged as high cost. And, they say, the use of the data raises thorny questions that should be debated publicly, such as: Should a person’s rates be raised because algorithms say they are more likely to run up medical bills? Such questions would be moot in Europe, where a strict law took effect in May that bans trading in personal data.

This year, ProPublica and NPR are investigating the various tactics the health insurance industry uses to maximize its profits. Understanding these strategies is important because patients — through taxes, cash payments and insurance premiums — are the ones funding the entire health care system. Yet the industry’s bewildering web of strategies and inside deals often have little to do with patients’ needs. As the series’ first story showed, contrary to popular belief, lower bills aren’t health insurers’ top priority. …

*****

You Snooze, You Lose: Insurers Make The Old Adage Literally True

By Marshall Allen

ProPublica (11/21/18)

Last March, Tony Schmidt discovered something unsettling about the machine that helps him breathe at night. Without his knowledge, it was spying on him.

From his bedside, the device was tracking when he was using it and sending the information not just to his doctor, but to the maker of the machine, to the medical supply company that provided it and to his health insurer.

Schmidt, an information technology specialist from Carrollton, Texas, was shocked. “I had no idea they were sending my information across the wire.”

Millions of sleep apnea patients rely on CPAP breathing machines to get a good night’s rest. Health insurers use a variety of tactics, including surveillance, to make patients bear the costs.

Schmidt, 59, has sleep apnea, a disorder that causes worrisome breaks in his breathing at night. Like millions of people, he relies on a continuous positive airway pressure, or CPAP, machine that streams warm air into his nose while he sleeps, keeping his airway open. Without it, Schmidt would wake up hundreds of times a night; then, during the day, he’d nod off at work, sometimes while driving and even as he sat on the toilet.

“I couldn’t keep a job,” he said. “I couldn’t stay awake.” The CPAP, he said, saved his career, maybe even his life.

As many CPAP users discover, the life-altering device comes with caveats: Health insurance companies are often tracking whether patients use them. If they aren’t, the insurers might not cover the machines or the supplies that go with them.

Host of tactics

In fact, faced with the popularity of CPAPs, which can cost $400 to $800, and their need for replacement filters, face masks and hoses, health insurers have deployed a host of tactics that can make the therapy more expensive or even price it out of reach.

Patients have been required to rent CPAPs at rates that total much more than the retail price of the devices, or they’ve discovered that the supplies would be substantially cheaper if they didn’t have insurance at all.

Experts who study health care costs say insurers’ CPAP strategies are part of the industry’s playbook of shifting the costs of widely used therapies, devices and tests to unsuspecting patients. …

*****

TED Talk — Government Surveillance Of The Population Is Happening, And Going To Get Worse

You want to look through your target’s eyes. You have to hack your target. You have to hit many different platforms.